Guatemala Coffee Experiments

Written on January 10th, 2018 by Griffin Hall

In mid-November 2017, I lived in the Acatenango Region of Guatemala for five weeks. I was invited to perform experiments in a wet mill to improve the post-harvest fermentation phase of coffee processing.

Check out the data!

(Underlined words are hyperlinks, so click on them! )

These data were recorded in Spanish, so let me know if you need a translation.

During my stay, I lived in a nice house on the finca (plantation) only a few kilometers from the bases of the Acatenango (dormant) and Fuego (active) volcanos. These ones!

The five weeks gave me much to write about, but for you Tl;Dr types- here is what I learned in a nutshell.

1. Most coffee people here are aware that climate change is threatening production. Managers realize they must adjust their practices, and this includes incorporating scientific research and methods. Yet, the lack of formal education and resources (both human labor and material) makes it challenging to perform true scientific experiments in this setting.

2. Coffee is processed by only a handful of people who work long hours for 5 or 6 days a week at the mill.

3. Workers usually don’t get to consume the coffee that they process, because it is too expensive. They mostly drink Nescafe.

Ok, you want to learn more?

I just ask you remember one key thing:

1. Fermentation is a strictly anaerobic process.

There is no such thing as aerobic fermentation. The misuse of the word fermentation is rampant in the coffee world and incorrectly suggests we actually know what is happening during this phase. In reality, we only know that there is an entire suite of microbial metabolisms occurring. Some of these require oxygen, and others don’t. The details remain mostly unknown.

I believe that characterization of the microbiota will become essential knowledge if coffee producers truly wish to control and improve their wet processing method, and overall be resilient to changing environmental conditions.

Since I want to keep this focused as much as possible on my experience (aka less like a textbook), here are useful links to background info. Study up.

* Coffee fruit anatomy

* Coffee fruit’s fate after picking (wet or dry method processes)

* Why “fermentation” is used (to convert the mucilage from insoluble to soluble substance)

* Guatemala's coffee history

Making these modern adjustments will be difficult for some, because coffee producers have always relied upon traditional methods to grow and process their product. Yet, some producers are early adopters of simple but quantitative methods in the hopes of producing a more consistent product. The most savvy people often draw influence from wine production methods, which are pretty effective in controlling post-harvest conditions. The coffee fermentation step is becoming especially scrutinized. A certain company sells specific yeast strains that can be added to a batch to help homogenize the fermentation product.

Before I arrived, my bosses bought some, but were unsure how to best use it. This is where I came in- I was asked to come to specifically test how under what conditions the yeast works best to reduce fermentation time and/or improve coffee quality.

I am by no means a fermentation expert, but I have decent knowledge of plant/microbiology and experimental design. I was honored to be asked to come work in Guatemala, but was slightly nervous that I was underqualified.

I arrived in Guatemala at night with two backpacks, and a mixture of nerves and excitement.

11/14-11/16

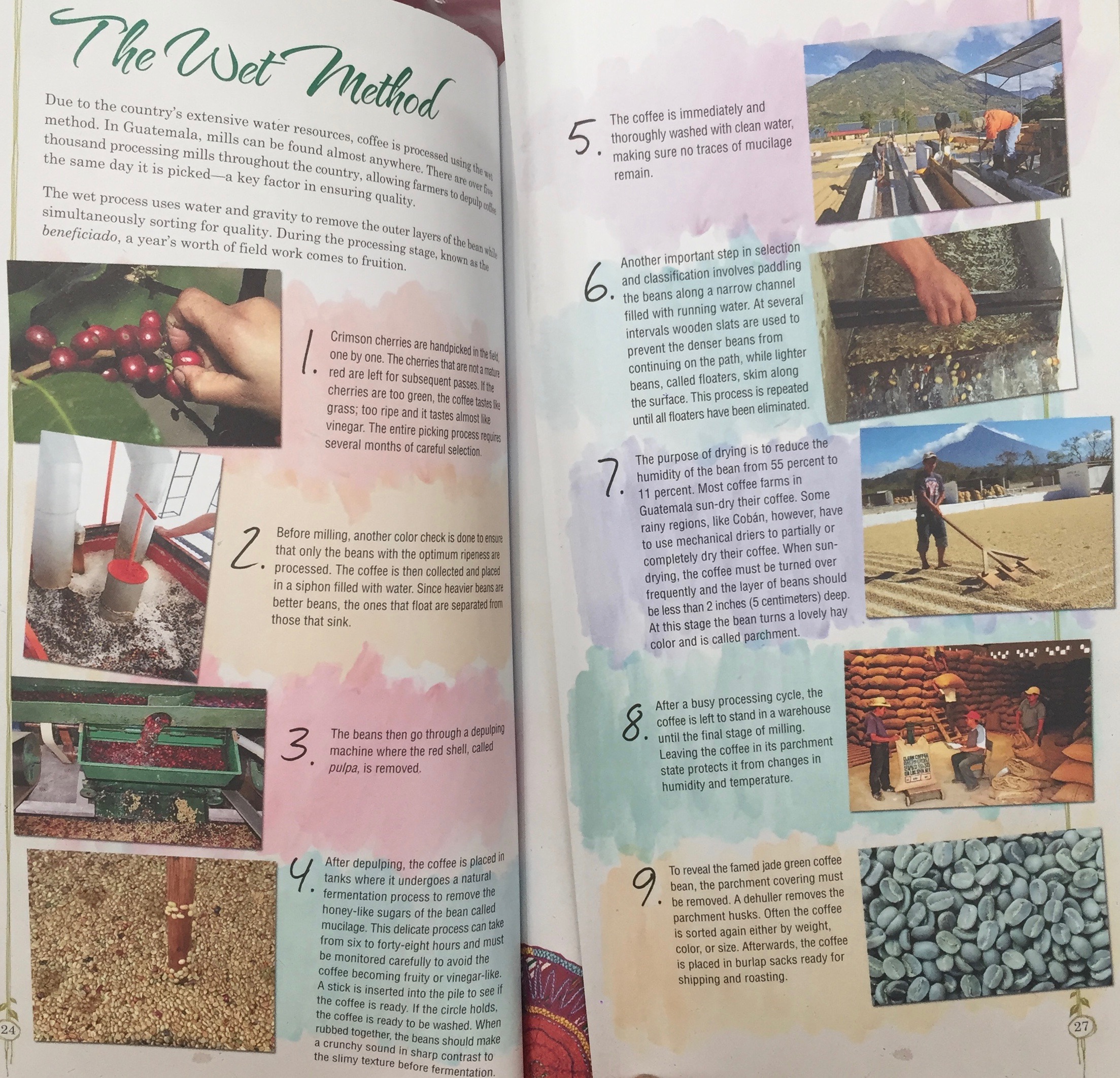

I spent the first three days learning how coffee is wet processed here.

The general process goes like this:

Every mill has its own quirks. Here, days go like this;

1. Coffee fruit picked throughout the day by entire families.

They and their harvest arrive at the mill in dump trucks between 3 and 7 pm.

They and their harvest arrive at the mill in dump trucks between 3 and 7 pm.

2. Families weigh their bags by the “quintal” (100 lbs.)

This data is recorded by a mill administrator and used to determine payment, which occur every 15 days.

3. Fruit is dumped into giant tanks of clean water.

Here, the first separation of quality occurs. Any “floaters” (over-ripe or otherwise defected fruit, usually due to pest infestation or disease) are scraped off, depulped, and sent to concrete fermentation tanks.

All pulp is sent through PVC tubes to a truck outside the mill. The pulp will be sent to nurseries for use as compost.

4. The remaining, higher-quality (more dense) coffee is washed out of the tanks, to machines called “cribas” that classify beans based on size. The ranking goes 1A (largest), then 1B, 2, and 1C (smallest). I never found out why 1C isn’t before 2…

Cribas are rotating cylinders with holes that allow only beans under a certain size to pass through. In the first criba, 1A cannot pass because it is too large. Any remaining whole fruit is passed through a depulper, which uses pressure to separate the bean from its pulp. These beans pass through yet another 1A criba (a backup), then rejoin the other 1A beans in their own channel. These are are sent to the 1A fermentation tanks.

Keep in mind that fruit arrives in various stages of maturation. Extremely mature fruit has already been depulped, so some beans are already free. These fall to the bottom of the channels as they pass, and are directed through the a series of pipes of a Canyon Colorado (shown below). This nifty system effectively separates free beans from pulp, with the help of gravity. Pulp floats while beans sink.

5. The rest of non-1A beans pass through a second criba that selects for 1B. The process goes the same as for 1A, just with cribas adjusted for smaller bean size.

6. The same process is repeated, for 2,1C (the smallest seed classification), and Nata (the bunk stuff… aka future Nescafe)

7. Beans are fermented in open concrete tanks.

They definitely are not sterile, but they do the job.

8.After fermentation, beans then washed to remove mucilage.

They look like this after washing.

9. Washed beans are placed out to dry, either directly on the patio, or in wooden boxes with metal screen bottoms.

Either way, someone needs to periodically mix the drying beans to homogenize the product. Here, it's Jose Juan.

After about a week, once the moisture content reaches about 11%, beans are bagged and sent to the on-site bodega for storage until pick up.

It was tough to get a video that truly conveys the feel of the system, but here is one angle.

Each day, multiple tons of coffee are processed. Yet, all this is accomplished by a very few number of dedicated employees. The average worker seems to arrive around 6:30 am, and some do not leave until 8 or 9 pm (if there is no problem/ delay…which there often are).

Introducing: The Team

Jairo Sigüil, Wilfido Galindo, Alberto Wiwi, Hilario Jimón, Don Layo, Griffin Hall (the only english speaker), José Juan Alvarez, Derick Xía, Eliseo Calléjas, Juan Cos, Warner Cos, Francisco Pérez (El colocho)

I didn’t get to interact with all, but here are mini bios of some.

1. El Colocho

Records harvest weight, and uses a portable refractometer (Brix) to record sugar content of the fruit. Here, mature coffee has between 18-21% sugar.

El colocho doesn’t have an email address, but he does have a cell phone. He has been working at the mill for 44 years, since he was 13. Back then, he was paid 50 Guatemalan cents a day.

2. Hilario

Arguably the man of the mill. He is involved in the entire process. He uses wooden spades to direct the coffee from the initial tank to the siphons, turns on/off all machines, and oversees that the entire process runs smoothly. He mostly oversees the “1A” process, which is the most valuable product. He also washes coffee in the morning after fementation, and knows how to fix many of the machines. His son (also Hilario- not pictured) is mostly responsible for overseeing the classifications (1B,2,1C,Nata)

3. Wilfredo

Drying master. He monitors post- wash pergaminos until seeds contain humidity ~10%, which can then be sent to a dry mill for further processing.

4. Juan (did not appear in the group photo)

He reportedly walks ~6 km to/from work each day. Has been doing this for decades. When I heard the story, my first thought was “why doesn’t he get a bike??”.

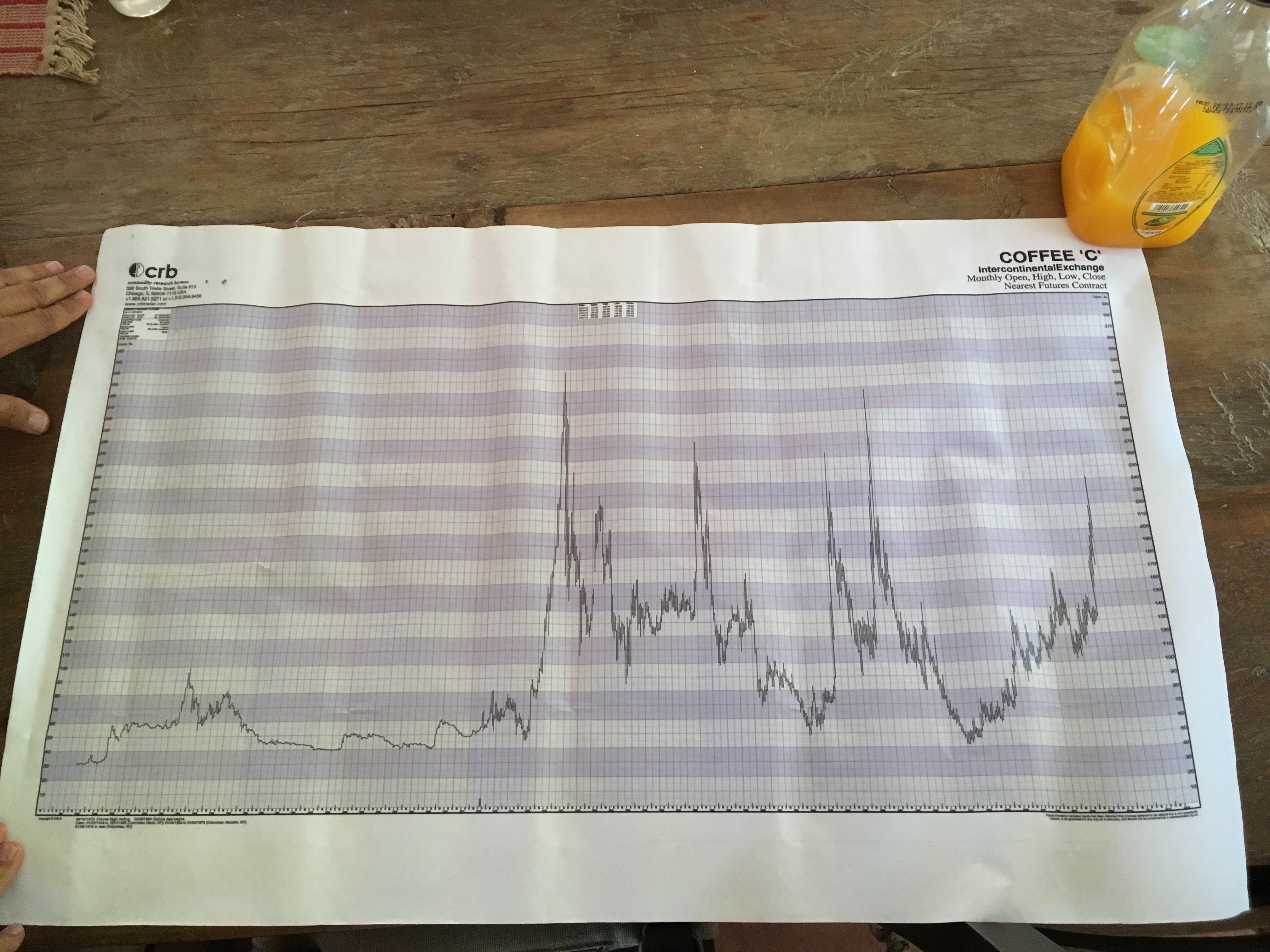

Despite the efforts of these diligent workers and the many field workers, producing quality coffee is always a challenging and uncertain business. One of the first things my boss told me was that climate change is noticeable affecting them. Weather is becoming more variable, including more frequent severe weather that can dislodge fruit from branches, wash away soil from roots, and spread fungal disease. Hectares of prime farmland are disappearing. To attain similar conditions as before, they must plant at higher elevations, but obviously a mountain only goes so high.

It’s seriously no joke- some research predicts that half of arable land for coffee will disappear by 2050.

In 2011, this company was hit hard with a “Roya” coffee leaf rust outbreak that reduced their production by 75% of their previous year’s crop. They still are climbing back, but still significanly below prior production levels

11/20/17

The first experiment begins tonight after depulping! I’m excited and probably look like some starry-eyed idealistic millennial, full of hope to change the industy for the better. I’ve been assigned an assistant- Jose Juan Alvarez. Here he is with experiment tubs.

He works as a farm advisor for Anacafe ,and has been interested in learning about post-harvest processes for some time. We began a basic experiment that compares the Lalcafe Cima® yeast (aka some undisclosed strain of S. cerevisiae) vs. bread yeast we bought in town vs. a control. I got the bags of yeast here.

We took various measurements for all experiements- see the data sheet near the top of the page complete disclosure!

For each experiment, we used 10 kg of bean in each big blue bucket.

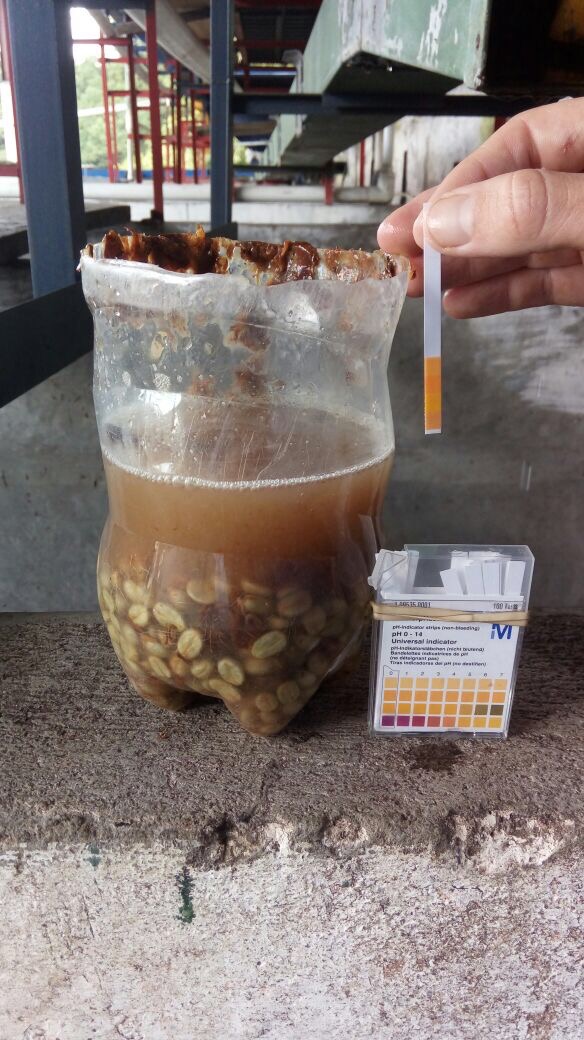

For this test, we let it run until it was at wash point. Traditionally, the stick method has been employed to determine when a lot is ready to be washed. When no beans fall until the holes, the batch is ready for washing.

However, we used a slightly more modern method of pH strips to determine when to wash (about pH 4). I know…so fancy.

We also counted the number of beans per pound, to calculate weight lost between various processing phases.

That night at home, I tried to do some Internet research to learn what environmental factors could affect fermentation. I immediately missed having connection to a university internet- I could only read paper summaries (called Abstracts). ☹

11/21/17

My job gave me weekends off, so I traveled around some. Over the weekend, I met a very small producer in San Miguel, at Lake Atitlán. He told me a tale of the MoscaMed program. His eyes were bright as he explained he had no doubt the program is a conspiracy, created by México to purposefully spread the Roya in Guatemala to relatively elevate their own industry. How scandalous!

However, when I asked my boss, he immediately denounced the claim, saying the fly doesn’t do much to spread the Roya.

By the way, the Roya is no joke. There are dozens of varieties, and it often mutates after each fungicide application. Boss believes there may be a cure, but the fungicide industry won’t let it out… hmm…

11/22/17

I have determined that I need to change my mentality of what it means it work in rural Guatemala. My USA work mentality isn’t very compatible with a much more lax culture of workers who aren’t accustomed to being totally precise. I find myself frustrated, feeling like I am the only one who understand why it's important to be precise for the experiments. For example, the workers don’t understand why washing a treatment and control batch at different times would be problematic. I feel silly being frustrated and occasionally stressed amongst these happy and relaxed people. Ok, I just have to roll with it- this is the third world. These people have never been taught how to do science- this is what trying to do experimentation in the third world looks and feels like. Good life lessons here at the mill.

Today, I became really curious about flies. Flies! The hidden answer. When I tap the bucket, dozens arise. More appear from the yeast bucket. Do they eat the yeast? Could this reduce microbial growth and therefore slow fementation? I’m privately nerding out..

11/22/17

It seems that the results show that the bucket with more flies arrived at its wash point more quickly than the other batch. Maybe the flies somehow accelerate growth? I don’t have access to any fine mesh net to exclude them, so my only option is to cover the bucket with a thick black plastic sheet.

This will, of course, also greatly reduce oxygen access, but I am too curious to not do it. The nice thing here is that I have nearly total freedom to test what I want. If I had enough resources, I could have been living a scientist’s dream!

I have another theory about the flies. Perhaps a higher sugar concentration leads to faster fermentation. Having more sugar definitely attracts flies, so maybe this this also speeds up the process. Alternatively, maybe there is no effect? I really wish I could do combination experiment, but we don’t have resources..

Today I also learned that when coffee is more mature to begin with (aka higher Brix), more pulp ends up in the fermentation tanks.

11/23/17

Today, we shifted a we began to determine wash point with a mixture of pH and traditional knowledge. After 18.5 hours of fermentation, the pH of covered bucket was 4, and pH of the open bucket was 5. We made the change because Hilario said that, even though pH was low enough for the covered batch, it still wasn’t ready because of touch (the honey didn’t come off easily). We waited 1.5 hours, and then washed.

The differences between coffee origin and consumer countries are vast, and I don’t think this gets enough attention.

As part of this blog, I want to show people what the culture is like in a coffee producing country. Everyday, Jose Juan and I travel the same route through the town of San Pedro Yepocapa. I took a 10 min video of Yepocapa to show people where these coffee workers come from.

If you don't have that patience now, check this speedy one out.

Not having a gimble makes me realize how bumpy the road is! In addition to the cobblestones, this town of 20,000 people has 20 speed bumps.

11/29/17

Newcomers on the finca! I’m not the only foreigner, though they still can’t call anyone else Gringo (it replaced my real name within a few days of my arrival). Japanese buyers from OCC have been here the past 2 days renewing a contract for Geisha (a pricey variety with a delicate taste). I accompanied these two men and an administrator to give a tour of the mill. I translated Spanish to the one who spoke English. It’s good to spend time with people who have fresh eyes for something you have become used to. Seeing the men marveling at the dozens of people squished into the back of a truck on the dirt road awakened memories of when I felt the same thing- witnessing many ridiculous and unsafe conditions of daily life.

I realized how quickly I became accustomed to this culture- and once again, how humans are quite adaptable. We are the most invasive species, after all.

On our tour, we spoke of how different things were in our respective countries. We also discussed how we would use more sterile methods if we were in charge. That night, we drank OCC instant coffee.

Then, I chatted with one of them about science and coffee while watching the Fuego volcano erupt from our neatly trimmed lawn.

11/30/17

We are about ready to cup our first samples! I explain the process a bit further down.

We have found, so far, that Lalcafe yeast is ready to wash after 18-21.5 hours. Covered buckets are ready to wash after 20 hours. Covering creates anaerobic conditions, which definitely changes what microbial metabolisms occur. I still hold the deep desire to ID the microbes, especially after talking to the Japanese guy last night. He holds a M.S. in Ecology and has used 96-well plates with microbial digestion to test soil diversity. He has no plate reader here, so just takes a photo- but it is still informative. (More improper science in coffee land.) He noted that this region has lower microbial diversity compared to Jamaica, no doubt due to the presence of volcanic ash here

Now that we really have our work schedule down, Jose Juan and I are performing multiple experiments each day. Today, we began one that compared stirring the batch with a big wooden spade every 2 hours vs. not, as well as an experiment that compared no pulp (control) vs. 5% pulp (1 lb) added vs. 5% pulp (1 lb) + Lalcafe yeast added.

I’m still keeping my eye on the flies. I partly hate them because they bite (they are actually mosquitos, just not the same species that are in the USA..) and their marks itch.. but they also inspire curiosity. Today, there are more flies around the covered- only bucket. They can still definitely detect volatile chemicals emitted from the fermenting beans because it is not a totally sealed environment. I keep wondering.

12/4/17

Another newcomer! I’m now sharing my room with Jorge.

(Pictured on left)

Jorge also works for Anacafe, and will stay with me for a week. He specializes in post-harvest processes (like fermentation) and it’s great to have another person who actually knows how to manage experiments.

Workers accidentally spilled water in the patio on one set of drying beans, but it’s not bad enough to re-do the experiment. I don’t worry about this improper science anymore, which has allowed for a lot more enjoyment.

12/11/17

Today I had the privilege of attending the Coffee cupping session of our samples at Anacafé. There are still many samples that are drying, and will be cupped after I leave Guatemala. I had attended a handful of informal cupping sessions at Bay Area cafes, but it was new to attend one that assigned formal scores that involved meticulous notes.

We submitted our green bean samples, which were roasted the day of cupping.

The cuppers are all professional Q graders (the highest certification) who cup many dozens of samples a day. They must follow a restricted diet around when they will cup- this includes no alcohol or tobacco. Here is a video of them in action. Yes, the slurping is necessary- it creates a mist that evenly coats all surfaces in their mouths.

12/14/17

My depature date is looming and we are squeezing in the last of the experiments. They are mostly replicates of previous tests. I’m just trying to make the data a little stronger. When I leave, Jose Juan will fully take charge of monitoring the remaining drying samples and ensuring their delivery to Anacafe after the holidays. He must also counting dry beans and record the data. When we discussed the tasks he would do, I realized that no one else at the mill (besides maybe El Colocho) would be able to do this. It dawned on me that I had no idea how many mill employees had attended high school, nor how were even literate (it’s a country with a 75% literacy rate).

Wrapping up:

I’ve spend the Holidays back in the USA and wish I had a more definitive end to my blog. Something like- “…and we discovered the yeast is the best thing ever! Incredible gains!”. For now, I’m waiting on my boss to email me the final cupping scores.

Several workers asked when I would return to Guatemala. I had to admit that I don’t know when, or even if, I will.

I would love to return. I found the culture to be overwhelmingly warm and welcoming. I miss seeing people greet each other in passing on the street. Values generally do not include climbing a sort of corporate ladder, but rather lie primarily in their religion, and caring for their loved ones.

I was admittedly nervous to arrive since I had read countless horror stories online before the trip. I am happy and feel fortunate that I didn’t encounter any ill will. This is not to discount the reality that Guatemala is a country that has its problems and danger.

This unfortunate reality exists because money is hard to come by, and prices for everyday needs aren’t as low as one might think. (I think México was actually cheaper to travel in.) Still, it is a shame that much of Guatemala’s image is dominated by fearful stories. I encourage people to visit if that have an opportunity- it is a land of breathtaking natural and cultural beauty. Learn some Spanish before you go, and you will find the experience that much more delightful.

I hope I can continue to be involved with coffee and research. I am excited about the future of the industry, which seems to be making a push towards progression of their practices. Thanks for reading this blog. When you next bean up with a cup of absolutely bomb and potent coffee, consider taking a moment to reflect where it came from, and the various players who helped bring it to your mug.